In the evening I seek moments of serendipidy. I steal away to a room where alone, I turn on my computer. Just a brief search, I tell myself. I search for Things. My floor is littered–towering stacks typify my interests– books, magazines, folders opened filled with tearsheets. These days there are mostly pictures of vintage designer clothing. I seek something gorgeous from another time and place, some garment loved and preserved for its beauty, its timeless elegance, its superior craftsmanship. “C-H-R-I-S-T-I-A-N, ” I type, “D-I-O-R.” At the auction site amazon.com, I enter a favorite keyword phrase and punctuate it with “Return.” I begin my search with limited expectations but hoping to find something to own and wear that I could never have afforded when new.

In the evening I seek moments of serendipidy. I steal away to a room where alone, I turn on my computer. Just a brief search, I tell myself. I search for Things. My floor is littered–towering stacks typify my interests– books, magazines, folders opened filled with tearsheets. These days there are mostly pictures of vintage designer clothing. I seek something gorgeous from another time and place, some garment loved and preserved for its beauty, its timeless elegance, its superior craftsmanship. “C-H-R-I-S-T-I-A-N, ” I type, “D-I-O-R.” At the auction site amazon.com, I enter a favorite keyword phrase and punctuate it with “Return.” I begin my search with limited expectations but hoping to find something to own and wear that I could never have afforded when new.

A single line pops across the screen before me: “Opera Coat.” Immersed in the technology of my time, I react with measured precision. A click. A double click. The screen displays still images, most of which typically disappear in a flash as I move through this virtual bazaar. But not tonight. In a blink, I am wide-eyed facing my Technicolor dream coat.

I am the only one to see this. I am convinced of it. I am the only one who knows what this is. A seller has listed her mother’s Christian Dior Opera Coat. It seems to me that we are alone together with the coat. As I read breathlessly, a story begins to unfold. “My father, David Nemerov, purchased this coat from Christian Dior himself in 1946 for my mother, Gertrude. He was the Chairman of the Board of Russek’s Fifth Avenue.” I feel the electricity of instant recognition. I know this name. I look for the “Ask Seller a Question” link and consider briefly. “Hello,” I type, “I am an artist and teach art at a university. I recognize your name. Are you related to Diane Arbus?” I click again to Send. Eager–urgent for a response, I wonder how long will it take.

While waiting. I muse back to when I started collecting vintage clothing. In art school I accompanied my boyfriend to the Salvation Army thrift store in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Instead of stretched canvases, he was working on paintings that used overcoats as their substrate. On any given day he would select a heavy garment, ones with ample size and scale so that when he covered them with his recipe of modeling paste and gesso, its batlike form would create unexpected shapes on the wall. Attacked with abstract color patterns of fantastic highways and arteries, they would hang from their tails like so many brightly colored carcasses skimming the vertical surface. As he browsed the racks contemplating a purchase, I strolled the store, pausing to stroke cashmere beaded sweaters and 3-piece tailored suit sets from the 1940′s with labels from Jay Thorpe or Best & Company, now-defunct stores in New York City.

As I gravitated towards photography, my personal heroes became three artists who created black-and-white documents of America: Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and a mesmerizing woman named Diane Arbus. Arbus shocked me with her remarkable and unexpected portraits of nudists in their living room watching TV, a grimacing boy gripping a toy hand grenade, triplets on a bed wearing identical white blouses and headbands, a Jewish giant at home with his parents, two men dancing together at a Drag Ball. The young Diane Nemerov Arbus working collaboratively with her husband, Allan—who is remembered for his TV role as a psychiatrist on M.A.S.H.—did commercial work as well: fashion photography for that very same Russek’s department store ensconced in a Stanford White building at the intersection of Thirty-Fifth Street and Fifth Avenue and for many magazines, including Vogue. Not long after her father gave her mother a black velvet opera coat by Christian Dior, Diane and Allan would publish their first photograph in the May 1, 1949 issue. In the center of the picture are a man’s and woman’s (wearing white gloves) clasped hands. She is dressed in black-and-white polka dots and a light-colored feathery helmet of a hat. His profile is sheared off the right side–an asymmetrical gesture that would all but disappear in her later work. By the late 1950′s Russek’s had closed but Arbus went on to do considerable magazine work before developing her uncompromising signature style exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in 1967 and in a retrospective soon after her death in 1972.

I click on my email. There is a message from REN. “Yes,” she writes, “I am Diane Arbus’s sister.” Emails fly back and forth between us and the coat begins its journey back east from the southwest. My excitement is uncontainable. I run to a bookshelf grabbing monographs and biographies. I reread a chapter that even describes the seller of the coat. She is an artist. I learn the date of her birthday and make a mental note to send flowers and, as requested, a picture of me wearing the coat.

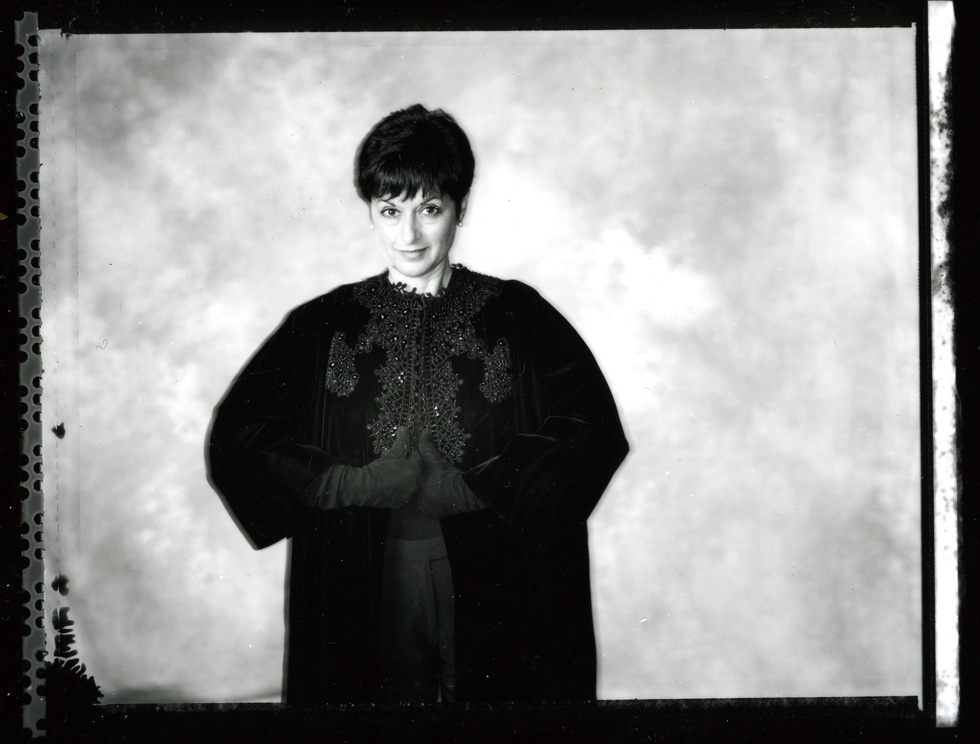

FedEx delivers a box. On the outside it is clearly identified as a computer scanner. It is too light for that mechanical peripheral and the return address hints at its true contents. I lift the coat from its bunting of bubblewrap, tissue paper and small plastic supermarket bags. The heavy, shiny black velvet modulates between highlight and shadow as the folds fall away. I note that a large white Christian Dior label bears a couture identifying number in the upper right corner—16262—and there is a smaller black label stating Made in France below it. The hand slides across the low, smooth nap searching for the seams that would connect a front to a back. Cut all in one, the front panels form dolman like kimono sleeves ending at a 3/4 length with a deep—nearly six-inch—hem inside. There is a gusset under the arms; and the bottom of the coat is unpressed lightly rolled and stitched. I immediately and carefully remove those stitches allowing it to fall to its true length (thirty-nine inches.) Gertrude was my size, and as I slip the coat on and look at myself in the mirror, it seems to have been tailored for me. Gleaming jet beads—flat, round and facetted—encircle the collarless neckline embraced in passementerie, It is likely an example of the superb embroidery technique of Maison Lesage, working with courtiers in Paris since the 1930′s. With an over-the-shoulder glance to the Victorian tradition of black beading and soutache, everything Dior would design in the late 1940′s would influence American style for the next decade. The great swinging skirt foreshadows the A-line, balloon and trapeze styles to come.

As deep and black as the velvet exterior, a lining of brilliant emerald green shantung silk peeks out and glows like a beacon on a starless night. The coat is crinkly thick, stiff even, as if there is another layer of lining between the velvet blackness and the shimmering green interior. It swooshes around my knees. Warm, it is heavy enough for a northern winter evening on the town.

I feel enveloped in a mantle of magic and mystery as this glorious velvet cloak once handed to the department store magnate Nemerov by Christian Dior now covers me. And I notice there is something else on this coat. Something other than the three Bobby pins in the pocket. There are a few—-not many, perhaps 4—delicate, hardly visible strokes of oil paint on the edge of a sleeve —white, beige and, coincidentally, that fabulous green. I imagine that the artist, who would eventually sell this coat, brushed by a wet canvas or, returning from a reception for an art exhibit, passed through her studio and could not resist an adjustment to the canvas on an easel. As exquisite as this coat is, what makes my heart race is not that it is an example of Christian Dior’s astounding and influential collection for 1946-47. It may have been touched or even hugged by Diane, her poet laureate brother Howard, and their younger sister, the artist Renée Brown. A coat with a past– of a family provenance so profoundly talented as to provide a wellspring of inspiration—rests on my shoulders as I pass through the doors of a gallery to an exhibition of my own.